Kinda left the narrative thread hanging there, didn't I?

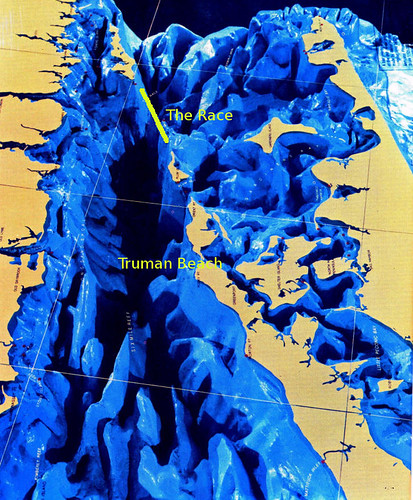

When last heard from I was motoring to Danford's Marina in Port Jefferson, shown below:

The marina is in the center of the map; the ferry slip, for the Bridgeport-Port Jefferson car- and people-ferry, is a bit to the left. Unless Google have changed the satellite image by the time you read this, you can see a ferryboat actually approaching the slip. I may have a bit more to say about this ferry later.

This image must have been taken during the off-season; as I approached, there were a lot more boats around than you see here, and many of them were big intimidating boats, including the doltishly-named Prediction, mentioned in a previous post, a boat larger than many New York apartment buildings. If it had been there when this photo was taken, we might have had to back off on the zoom.

My goal was to get the outboard on the dinghy fixed -- for the third time this summer. Danford's is supposed to do repairs, and a breezy young lady had assured me on the cell phone that such was indeed the case.

Once I tied up at Danford's dock -- for which one is charged $20 an hour, a fee I shamelessly skipped out on later, and without permission, too -- the mechanic turned out to be a pleasant young man, let's call him Lycon, who enjoys tinkering with outboards. He and a couple of dockside sages confirmed what I already knew: the carburetor was gummed up and would have to be taken apart and cleaned.

Lycon wasn't quite ready to undertake this task, though I think he might have made a good job of it. But he knew just who to call: Port Inflatables, specializing in inflatable boats like my dinghy, and small outboards like the one that powers it.

Port Inflatables was willing to send a truck to pick up the outboard, though they wouldn't venture out onto Danford's dock. I got the impression that Danford's could be rather stroppy about other people trespassing onto their turf. So I had to rassle the outboard out of the dinghy -- a sweaty effortful business -- and then up Danford's dock and across Danford's parking lot and out to the sidewalk, which took a good deal more sweat and effort. Outboards, even Japanese outboards made of aluminum foil and sushi, are heavy, and awkwardly shaped to boot.

Port Inflatables showed up promptly, as promised, in their truck, and took the poor outboard into their care. They made a good efficient impression. "We'll call you tomorrow," Inflatables said.

I could hardly have expected better -- this was mid-afternoon, or perhaps a little later -- but even so, the line had an ominous ring: I'll see you when I see you. Don't call us, we'll call you.

But what can't be cured must be endured. So I resolved to use my time ashore well. I asked where I could find a grocery store. Blank stares all round, which became blanker still when I mentioned that I would be on foot.

The nice people who work at Danford's don't live anywhere nearby, it turns out. They live in Five Towns or Massapequa or Huntington Bay and drive fifty miles each way to their jobs, and they never, ever walk around on the streets of Port Jefferson.

Finally someone dredged up a memory of a convenience store, owned and staffed by hard-working entrepreneurs from the Indian subcontinent, a ways up Main Street, which runs away from the waterfront and climbs a rather steep slope to the bluffs behind the town. Thither I set off.

Now I haven't really set the scene very well here. It's a hot, sunny, still day. I've been tinkering with the motor, and then humping it off the dinghy and up the dock, and at this moment I'm trudging up furnace-like Main Street with Long Islanders' SUVs blasting past me and blowing exhaust in my face, and I'm starting to feel a little strung-out and a little parched.

When what to my wondering eyes should appear, but --

A cool, shady, caravanserai whose actual name I forget; but let's say it was something like Captain Jack's Bar and Grill.

Some bars appeal and some don't. This one appealed very strongly. Its entire front was open to the street, but set back from it, across a sort of terrace, and you could see the folks sitting at the bar, well inside and out of the sun, and other folks sitting at tables, and they all seemed to have tall frosty steins of beer in front of them, which my usually hazy old eyes registered with preternatural aquiline clarity.

This is the place for me, I thought.

By this time I'm scruffy, not having shaved or showered in four days, and sweaty, and thoroughly disreputable looking, and there can be no possible doubt that I smell like an old plough-horse. But I sat myself down at the bar and pulled a book out of my pocket -- I never go anywhere without a book, and reading a book makes you less alarming when your grooming is not what it should be. And the sweet young thing behind the bar came over and I ordered one of those frosty steins of beer I had seen from the street.

The sweet young thing -- let's call her Phyllis -- produced my frosty stein with admirable alacrity, and then to my utter amazement engaged me in conversation.

She's maybe twenty, and I'm sixty-plus and looking every minute of it. and surely as far as

she is concerned I might as well be a dinosaur skeleton in the Museum of Natural History. But she took an interest in my journey, and plied me with questions, and even wanted to know what I did about sanitation on the boat, and wasn't grossed-out by the porta-potty.

Dear reader, perhaps you have a suspicious turn of mind. If so, let me reassure you: I do not flatter myself that Phyllis was coming on to me.

You're out on the water for a few days, and you start to have wild fantasies. In my slightly crazed Jack-ashore mood, I would have loved to think that Phyllis couldn't resist my threadbare charms, but it just obviously wasn't that kind of conversation. What was amazing me was her unusual curiosity and her openness.

Long Island is a very suburban place -- perhaps the most suburban place there is -- and suburban life is so impoverished, so limited, so narrow, so contrived and controlled, that its offspring usually end up somewhat atrophied. They don't understand any dimension of social or personal existence that they haven't already encountered in high school -- don't understand it, and don't want to hear about it. You mention anything they haven't seen on YouTube, or been told about by some slightly cooler coeval, and you get the Suburban Blank Stare.

But Phyllis wasn't like that. She didn't seem to be chafing at her circumstances, and longing to get over the wall. She was very much of her milieu as well as in it. But somehow she had escaped the lobotomy. She was quite keen to hear about the adventures of an eccentric, oddly-spoken and ill-groomed old man from New York, who blew into town on a far-from-fancy old boat and obviously doesn't have a pot to pee in, money-wise.

I can't tell you how much this cheered me up.

I had a second beer and then reluctantly left Phyllis to whatever life has in store for her -- and I hope it's something very nice indeed. I trudged up the hill, in the slightly cooler crepuscule, and found the Subcontinentals and bought a few necessities including some ice for the cooler, and trudged back to Danford's dock and, as already confessed, left without paying their robber-baron tariff and went to look for an anchorage out in the bay.

This entry is way too long already, and Day Four isn't even over.

That's because this was a turning point. I haven't really come clean about how I was feeling.

The dinghy motor failure -- third this summer! -- had convinced me I was cursed, numine laeso, hopeless. I was ready to take the boat back to New York and take the train to Maine.

Then I found Inflatables, or rather, Lycon found Inflatables for me. Inflatables gave me, on balance, a good feeling, and hey, it's only money. Then Phyllis made me start to think that what I had undertaken was worth doing and worth telling about, and most of all, a cell-phone conversation with my indescribably wonderful wife gave me a shot in the arm -- as she always does.

So I will suspend Day Four again as I putt-putt out onto the quiet shadowy waters, seeking a place to spend the night, a place that I don't have to pay for. The coming of the light today found me very dark, and now that it's dark, I'm feeling lighter again.